“Requiem”

by Anna Akhmatova

trans. by Don Mager

1935-1940

“You cannot leave your mother an orphan Joice”.[1]

No, not even alien heavens,

Nor the protection of alien wings,

I was with my people then—there

Where they, the wretched ones, were.

1961

IN PLACE OF AN INTRODUCTION

In the dreadful year of the Yezhovshina,[2]

I stood in line for seventeen months outside a Leningrad prison. On one particular occasion, someone “identified” me. Then a woman standing behind me with lips blue from cold, who surely never before had heard me called by my name, seemed to gain consciousness from a daze and spoke close to my ear (everyone there spoke in whispers):

Ah, can you describe this?

And I said:

—I can.

Then something like a smile slipped across what was her face.

1 April 1957

Leningrad

CONSECRATION

Before this grief, mountains bow down

And courses of great rivers bend

And yet prison bolts, on account of

Their “convict lairs,” their ghastly

Anguishes stay strong.

For some, fresh winds whisper,

For some, the sunset holds luster,

We who know none of that, hear

Only the shameful keys’ grating

And soldiers’ grim pacing.

Early each day, as if imagining it,

We passed through the city’s wilderness,

Its ghastly soulless corpse, to wait

Until the sun sank, the Nevá got dark,

And hope sang only from the far distance.

We the condemned . . . and suddenly tears erupt

From one who has been set apart

As if along with her suffering

Her very life was ripped from her heart,

But she too moves on . . . tottering . . . alone . . .

Where are the unchosen friends now

Of those satanic double years?

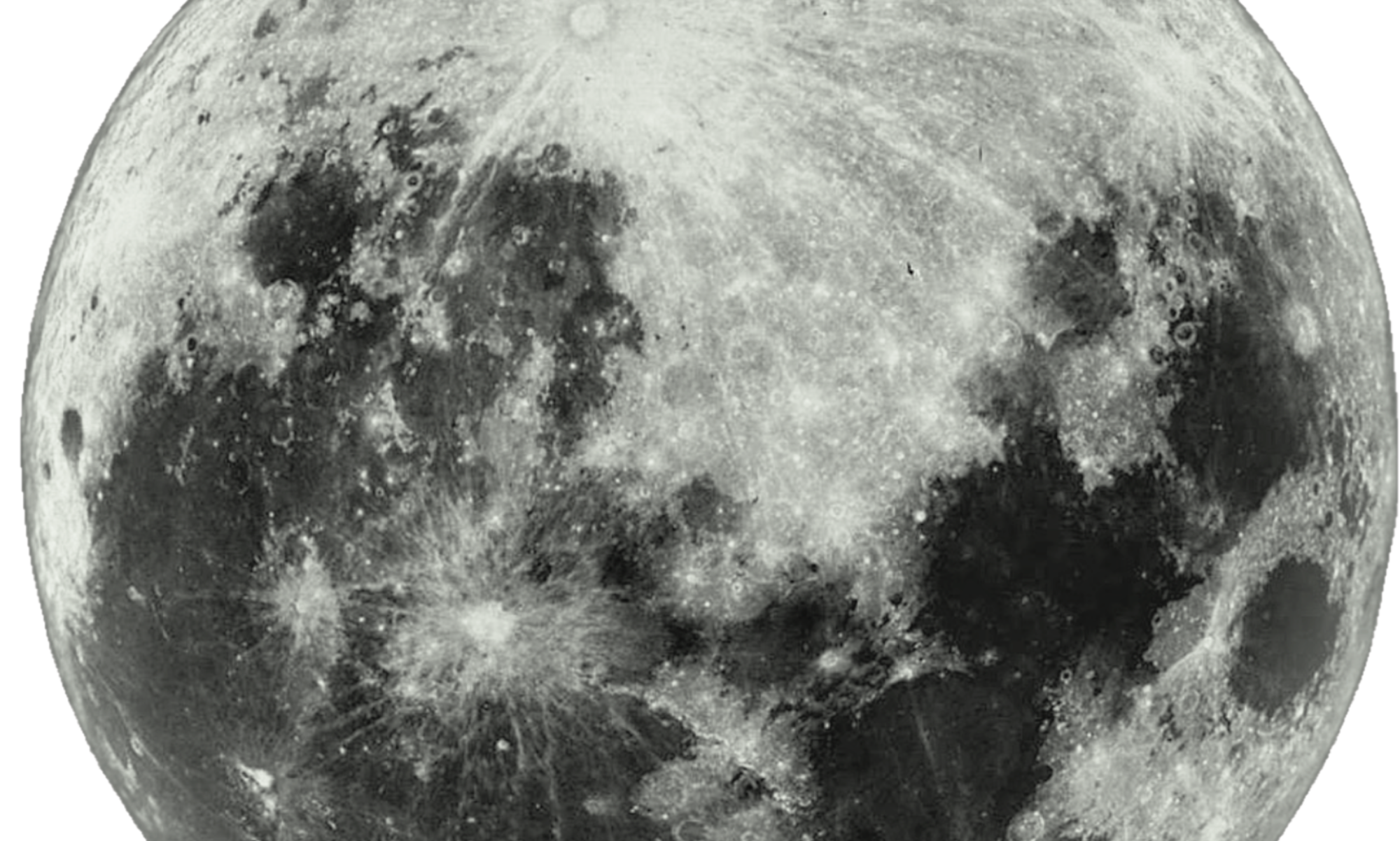

Do they survive in Siberian snows,

Gleaming like a lunar sphere?

To them, my valediction—my hello.

March 1940

PRELUDE

That was when only the dead smiled

Glad at last only to look down.

Uselessly they hung suspended

Outside their Leningrad prison.

And when crowds of the condemned

Were driven out of their despair,

They passed us by in tight order

And the whistle sang like steam.

The stars stood dead above us.

And Rus’§—guiltless—

Writhed beneath bloody boots,

Beneath the tires of Black Marias.

I

At dawn they came to take you away,

Carting you off; I walked behind;

In the dark room children cried,

And the blessed candle mourned.

Your lips cold from the icon’s touch. Still

The death sweat on your brow . . . unforgettable! —

Like the wives of Streltsy lancers,

I will wait beneath Kremlin towers.

1935

II

Quiet flows the quiet Don,

Into my room creeps a yellow moon.

Creeping, its cap cocked askew—

The yellow moon veers at the shadow.

This is a woman in pain,

This is a woman alone,

Husband dead, imprisoned son,

Pray for her now—for me, someone.

III

No, this is not I, this is someone else’s suffering.

I could never have borne it, so now, whatever happens

Shroud it with a cloth, put it to rest,

Empty the lantern, banish it.

Night

IV

They should have shown you then, mocker

Of cherished bygone friends,

Tsarskoe Selo’s cheerful sinner,[3]

How your lot happened.

Three hundredth person in line

Waiting along the Kresty walls[4]

And your ardent tears burn

Hot through New Year’s ice.

There the prison poplar sways,

Soundlessly. And the countless

Servile lives that end this way . . .

V

Seventeen months cry out,

Summoning you home again.

I had flung myself at the hangman’s boot.

But to my horror, you—son—

Are wholly and always a muddle,

And I no longer can comprehend

What’s human, what’s bestial,

And whether I crave your end.

Only, the color of dirt,

The clanking incense pot,

The track leading nowhere.

Now bluntly, forced into my eyes

And threatening sudden perdition,

A lone star towers.

VI

Weeks blow by, effortless,

What happens makes no sense.

And in your cell—son—

White nights are staring in,

Just as they stare down with

Hawk eyes that burn my eyes

Showing the towering cross

That signifies your death.

1939

VII

The Decree

The word plummeted its stone

Into my living breast.

Never mind, such misfortune

Somehow I’m fit to accept.

Today I have my work cut out:

Bring all memories to an end,

Wholly fossilize my spirit,

Start my life over again.

Or else . . . Outside my window,

Summer rustles with passion.

This, I foresaw long ago,

Light-drenched day, empty home.

1939. Summer

VIII

To Death

You treat all alike. So what are you waiting for?

I am prepared. In all my confusion.

I quash the lights but leave the door ajar

For you, so simple, so ravishing.

Take any form that you prefer,

Burst in, finish me off like poison,

Or steal in like a skilled robber,

Or blast me with typhus infection.

Or appear in one of the tales you dream up

Which give me a big pain in the head,—

Caused by the top of the blue cap

As the concierge whitens with dread.

To me, it’s all one. The Yenisei swirls,

The North Star gleams. And forever,

The blue gleam of my loved one’s eyes

Is blotted out beneath his last terror.

19 August 1939

Fontana House

IX

Surely insanity’s wing

Shuts up half my soul,

The quench of fiery wine,

The lure of the dark vale.

Now I see the task at hand:

Concede the victory,

And nurse it as my own

Another’s calamity,

Which does not even permit

To take myself away

(No matter how I entreat,

No matter how I pray):

Not a son’s awful eye—

Fossilized with pain—

Nor a day when the storms cry,

Nor prison visitation,

Nor the cool beloved hand,

Nor the lime tree’s trembling shade,

Nor the distant frail sound

Of comfort’s final word.

4 May 1940

Fontana House

X

Crucifixion

“Do not weep for Me, Mother,

in the dry grave.”[5]

1

A glorious choir has risen

And heaven melted in fire.

Ask Father: “Why am I forsaken!”[6]

Tell Mother: “Weep no more . . .”

2

Magdalena sobbed and shook,

The beloved John, a stone,[7]

And no one looks, or dares to look,

Where a mother stood silent alone.

Epilogue

1

I have learned how faces disintegrate,

How guardedly they peep at the world,

How cuneiform lines cut[8]

Into cheeks, incisive and hard,

How lovely black and ashy curls

Turn silver almost overnight,

How cowed lips turn into cracked smiles,

And dry laughs quiver with fright.

I do not pray for myself alone

But for all who stood the ferocious cold

And July’s bleak heat, beside me then

Beneath a red and blinding wall.

2

The day of remembrance comes round again.

And I see, hear, feel every one of them:

She who scarcely made it to the window,

She who can’t tread her native soil now,

She who would toss her handsome head

And declaim “The destination has arrived!”

I want to tell the names I knew so well

But the list is now beyond recall.

For their sakes, then, I weave a shroud

From pitiful bits of eavesdropped words.

And now wherever they may be, for them

Regardless what mischances yet may come,

While my exhausted mouth can utter still

The words a hundred million people feel

I will fondly cherish them, and pray,

Upon the eve of my burial day.

And should my homeland ever seek

To erect a memorial to me

I might consent to such a monument

With the condition: it not be set

Near the sea where I began

(My ties to it are long undone),

Nor the tsar’s garden, the stump of a tree,

Where shadows prowl inconsolably,

But here where I stood 300 hours

And the bolts did not release their doors.

Oh, even in death’s blessedness

I won’t forget the Black Marias,

The clang of the banging prison door,

An old woman’s yowl like a wounded boar.

And even in this Age of Bronze,

My tears know how to eat the snows

While pigeons gurgle distantly

And boats on the Nevá pass by.

Roughly 10 March 1940

Fontana House

[1] The epigraph in English is from James Joyce’s Ulysses.

[2] Ezhovshchina (“the EzhovTerror”) refers to the period of Nikolai Yeshiva’s tenure as head of the secret police, known for terrifying arrests, disappearance and show trials, 1937-9.

[3] Tsarskoe Selo was the imperial town outside Petersburg where the Tsar resided during the summer.

[4] The Kresty prison, or Cross Prison, in Leningrad was named for the shape of its floor plan. It was there that women could turn in parcels of food and clothing for imprisoned husbands, brothers, and sons.

[5] The epigraph is from a 9th century chant for Holy Week.

[6] Reference to Christ’s last words in Matthew 27:46.

[7] The Apostle John and Mary Magdalene were at the Crucifixion. In Renaissance paintings, they often are depicted as supporting the grief-stricken Mary, mother of Jesus.

[8] Vladimir Shileiko, Akhmatova’s second husband, was an Assyriologist and worked with original cuneiform tablets. She had opportunities to inspect the clay incisions closely.