So there’s this comedian out there who looks just like me. The resemblance is uncanny. He has the same bushy beard, the same scraggly brown hair, the same chubby belly. Even our voices sound alike, the same whiny baritone. He always wears a three-piece suit when he performs for some ridiculous reason, and I’ve only worn a suit maybe five times in my entire life. But even without the suit, people still walk up and bug me in public. “Excuse me,” they’ll say. “Has anyone ever told you that you look just like that comedian?” Typically I’ll smile, to assure them that I get it all the time and that they’re excused for asking. Then I’ll wait impatiently for them to work up the courage to finish the conversation. “You’re not actually him, are you?” They always have to ask before they can leave me alone, because even though you can tell up close I’m not the same guy, people refuse to believe it. They want me to be him. They want that brief brush with a celebrity they can talk about later with friends and family. They’re always disappointed when I confirm what they already suspect. “Sorry,” I say. “But I’m not who you think I am.” I feel as if I’ve let them down, somehow. Some people will still ask for a photo, and I usually let them take one. Once, a woman asked me to sign the comedian’s name on a napkin. “I know it’s not you,” she whispered, “but I can still pretend, right?”

For most of my life, this comedian wasn’t a problem. Only recently, now that he’s become famous, have I had to deal with the repercussions. People expect jokes from me all of a sudden, and I’m just not funny. It might not seem like a full-blown crisis, but when your own life is already a bit of a dud, the act of being recognized again and again for accomplishments that aren’t your own can wear on you after a while.

My friends think it’s hilarious, watching strangers come up and bug me in public. Almost like they get to pretend they’re in the world’s lamest entourage for two minutes at a time. I have this one friend, Josie, who will sometimes shout out the comedian’s name when we’re in public, to see if anyone might “recognize” me. She’s the one who first introduced me to the guy, who first pointed out the similarity. She’s also one of those people who laughs at just about anything, no matter how risqué or uncomfortable it gets. People need to loosen up a little, she claims. The comedian is certainly doing his part, what with all the stupid pranks the guy has pulled—recording vulgar voicemails for elderly celebrities, orchestrating a lewd baby photo caption contest, organizing an online petition to invade Canada.

“I’m just worried that stuff makes me seem like an asshole by association,” I tell Josie frequently. She only laughs.

“But you’re so not like him at all,” she assures me. “That’s why it’s funny.”

Sometimes I wonder if the comedian and I were separated at birth, somehow. I like to pretend he grew up as this really awful kid—tormenting stray cats, or stealing his neighbor’s mail, resealing it in another envelope and mailing it off to Tahiti or someplace. Like that’s the reason he’s a comedian and I’m not. But nope. I read this interview where he admitted that none of the vicious jokes about his childhood really happened. He was just this quiet and awkward kid. Which of course sounds exactly like yours truly. We probably had the exact same crummy adolescent experiences, halfway across the country from one another. I bet he spent his senior year without a car riding the bus to school with freshmen, and his gym classes tugging at off-brand gym shorts which were never the right length, and his prom night wandering aimlessly through the aisles of Blockbuster video. But then he went off to college and worked up the courage to join an improv group, then graduated and began to write for several sitcoms, then got a bunch of viral videos on YouTube, and then his own Netflix special, and then his own critically acclaimed quirky dramedy on basic cable. Whereas I remained steadily committed to mediocrity.

Maybe one day he’ll get a corporate gig performing at an IT consulting conference somewhere, and one of the attendees will come up to him and say, “Has anyone ever told you that you look just like this one Malware Specialist? He’s just so great at compiling his rootkit reports. Will you sign his name on my lanyard?” Until that happens, I guess I just have to deal with it.

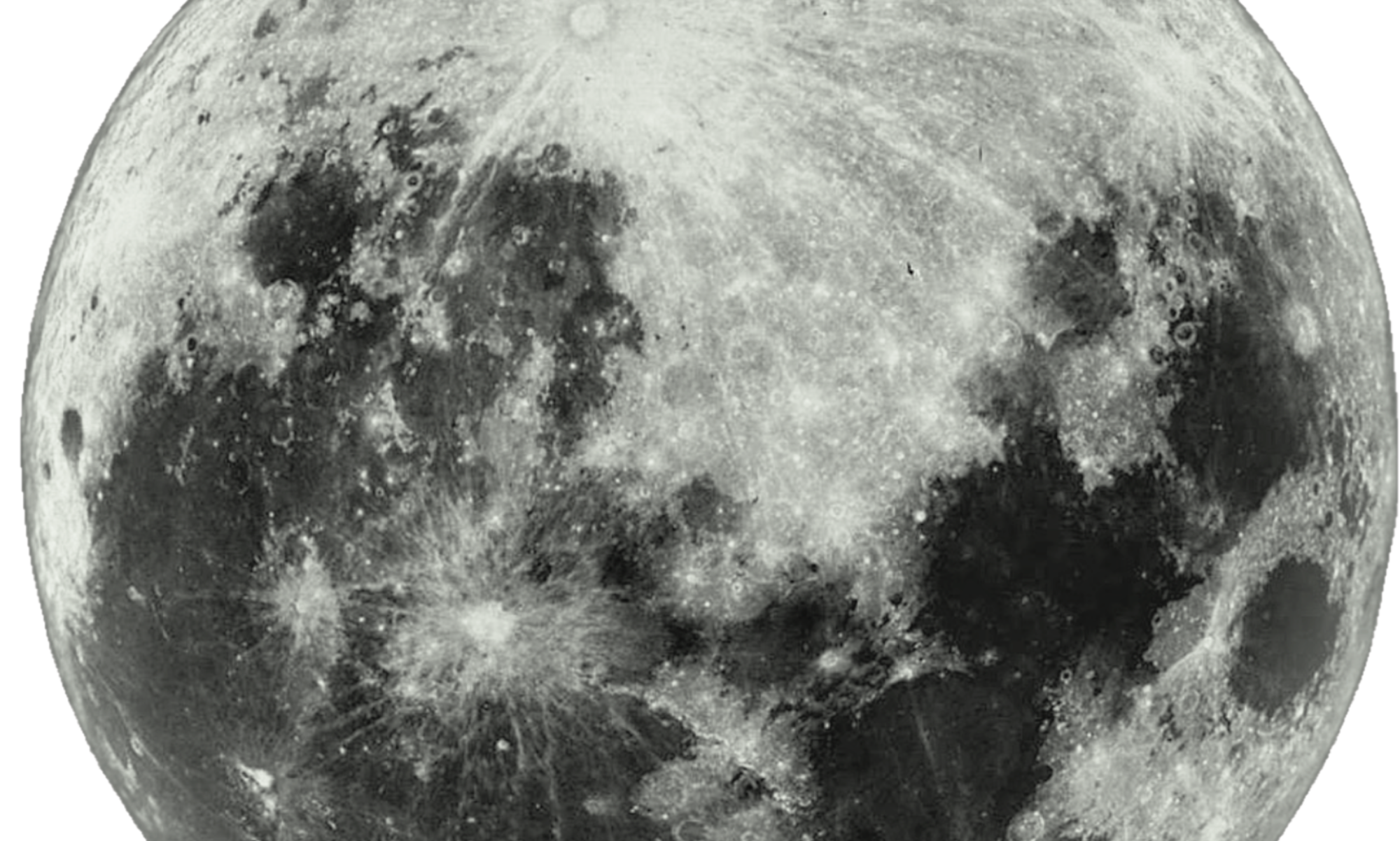

☽☾ ☽☾ ☽☾

Do you ever get the feeling you’d be better off if you never left your apartment? My friends are always dragging me out to bars, even though bars aren’t really my thing. And they always end up taking me to one of two places. Option A: one of those trendy, superficial bars where you pay a $10 cover charge and another $10 for a watered-down drink, just to stand in a corner with a few people you already know while incessant house music pumps away. Or Option B: a grimy dive bar with no cover charge where the watered-down drinks are only $5 and the music is more tolerable. But the thing is, the corner of the bar and the end of the night are the same at each place. Cramped, uncomfortable, and nothing new. Considering I dislike being around other people and confined spaces and the general act of being noticed, you’d think I’d have the sense to stop getting dragged out to these places again and again. I guess it’s tough to shake the feeling that if you don’t go out, there’s the possibility you’re missing out on something, or someone. That you’re being left behind.

These days, though, the only strangers I talk with at bars are the ones who insist on reciting the comedian’s jokes with me. They come up and shout out a setup, then expect me to provide the punchline. This is the part I’m really not on board with. Most of the comedian’s jokes are pretty vulgar. In my opinion he devotes an unhealthy amount of material to misogynistic jokes about his wife. Not the kind of stuff I want to be yelling in public. For a long time I refused to even familiarize myself with anything he did, but one night these two lug-heads approached me, and without so much as an introduction they both blurt out in unison, for practically the whole bar to hear: “Hey there, horsefucker! How about a pony ride?” Josie had to explain that the phrase was something the comedian yells out frequently at his shows. After that, I finally let her show me some of his standup, if only so I could tell when I was supposed to be in on a joke, and when I was actually being called a horsefucker.

So she picks out one of his specials for me to watch, and halfway through this one bit he does about kicking puppies, I turn to her and ask, “This is really supposed to be funny?”

Now that I’m more familiar with his body of work, I don’t understand how he gets away with so much. Every time he says something despicable, which is frequently—the Native American gibe on Late Night, or the autism riff at an award show, or the AIDS comment on Twitter—I think that might be it for him. His career will fade, he’ll go away and leave me alone. But he’s always able to explain it away as a joke. Comedy hurts, is his excuse, and lots of people seem OK with that.

“It’s supposed to be provocative,” Josie assures me with a shrug, one of those confident, commanding shrugs of hers that somehow always sway me and explain away just about anything.

“If it bugs you so much,” she’ll say, “tell yourself we’re laughing at him, not with him.”

I’ve been told that if the comedian truly bothers me, I should do something. Change. Cut my hair, shave my beard, lose some weight. But I looked like this before the comedian became famous, and I don’t think it’s fair to expect me to change on his behalf. I would feel off, somehow, if I changed how I look. It would make me a different person.

I’ve also been told I should go in the opposite direction and just embrace the whole doppelgänger thing. Become a celebrity impersonator and make some money, or at least start walking around in a three-piece suit asking for free drinks or something. Josie, who’s always been outgoing and vibrant and assured, everything I’m not, claims she was a total wallflower in high school until she started dying her hair and dressing like this pop punk singer, which completely changed her level of confidence. She seems to think that qualifies her to serve as my image advisor. I’ve tried pointing out it’s not really the same thing, since no one even remembers the singer anymore, but she still insists if I act more like the comedian it will help me come out of my shell.

“Try asking yourself, what would the comedian do?” she’s always saying to me. “And just see what happens. I think you’d be surprised.”

Once, we were out grabbing a meal at one of those burrito places, and this guy cut in front of nearly the entire line.

“Did you just see that bullshit move?” Josie said to me. “Man, I wonder what your comedian friend might say to him.”

She started prodding me in my side, and when nobody else did anything, just when it seemed like everyone was going to let him get away with it, I took a deep breath and walked up to the guy.

“Excuse me,” I said to him. “But did you know statistics have shown that eight out of ten line-cutters have smaller-than-average penises?”

“Huh?” he said.

“You just cut us all in line,” I told him. “Now the way I see it, you can either stay here, which would basically be you admitting to the entire restaurant your penis is extraordinarily small, or you can move to the back of the line where you belong, and we’ll all promise to forget about your tiny member.”

I was afraid the guy was going to knock my teeth out, but all of a sudden other people in line start backing me up and clapping in encouragement, and the guy actually moved to the back of the line. The whole thing felt like this major rush, this real big-time moment. I mean, it would have felt like a big-time moment if that’s what had happened.

But of course that’s not what happened. Come on. I’m not the type of person who would do something like that. Instead I just stood there, silent, debating what to do, until the guy ordered his food and left. Josie wouldn’t let me forget it, either. She kept shaking her head and chuckling at me throughout our meal.

“What am I going to do with you?” she kept saying, and I couldn’t tell if I loved her or hated her for it.

☽☾ ☽☾ ☽☾

People will do ridiculous things to meet other people. I used to think dressing up and pretending to be a famous person would be the absolute lowest possible way for me to try and meet a girl. That was before I tried online dating.

I say I tried online dating, but in reality there was much more attention paid to the online part than the dating part. I had an account, with a profile, and my profile theoretically interacted with other profiles. But very rarely did those interactions result in actual dates in the real world. I tried all the tricks people told me about—changing the filter on my photo, trimming a year or two off my age, but none of that helped. Probably because everyone out there was using the same exact tricks. If people assume you’re lying about who you are upfront, they’re not even going to give you a chance to show them the real you.

Then there was Josie’s advice, to play to my strengths. She—who by the way has no need for online dating since she’s always meeting these lawyers and bankers and account executives out at bars who buy her drinks and whisper in her ear—took it upon herself to act as my personal profile curator.

“It’s not enough just to look like the comedian,” she tells me this one time we’re scrolling through all the matches she insisted I could be getting. “Your profile must become him.”

“Meaning?” I ask.

“Make your profile funnier,” she says. “Write it up as if you’re actually him. Use his actual name, if it helps. His photo, everything. Then when you turn up as you, it’s like this pleasant surprise. A nice guy who’s actually normal, for a change.”

That’s not going to work, I explain to her. Not only is it totally disingenuous, but there’s also no way I can pull off the comedian’s brand of humor.

“Then let him be funny for you,” she insists. “Just steal some lines from him and put them in your profile. Some of his bits. Oh man, what’s that thing he says in his routine about internet stalking?”

“Internet stalking?” I say. “That isn’t really the look I’m going for.”

“No, no, it’s um—excuse me, he says. I couldn’t help but notice you from across the internet. Put that in your profile, I guarantee you’ll get a match.”

“That’s awful,” I say. “Nobody will think that’s funny.”

“It’s kind of funny,” Josie says. “And chicks love humor.” She picks my laptop up from my thigh and moves it to her own lap, then looks straight at me.

“I know you hate this,” she says. “And I know it isn’t your fault that this guy became famous. But I seriously think this will be good for you. Imagine there’s this whole different person hiding inside of you, and we’re just trying to get him to come out.”

So I let her update my profile with all these terrible quips from the comedian. Within 20 minutes there’s a match. Nice profile, the match writes. Wanna chat?

“Oh, we’ve got one already,” Josie yells. “And she’s cute, too.” With that Josie is off, typing as if she’s me.

Tell me your background, the other profile writes. What do you do? Make lots of $$?

I thought you might have already recognized me, LOL, Josie types. Don’t you know who I am?

No, but I’d like to ; )

“See,” Josie says, slapping my shoulder. “She likes you for who you are.”

“Josie—” I say, but at this point she has complete control.

You’re cute, she types. Maybe we should meet up for a drink, sometime.

I’m sitting there, staring over her shoulder, watching as little dashes flash on and off the screen while some stranger types somewhere. Staring and waiting for the response with this morbid sense of anticipation, even though I know what’s coming and how this will end.

I have much cuter photos if you want ; ) the other profile finally writes. Send PayPal account and I send more photos.

“Oh,” Josie says, and hands the laptop back to me. “Shit. I’m sorry.”

Typically with Josie I can never tell when she’s playing around or when she’s serious, and I honestly wasn’t sure whether or not she genuinely didn’t see that coming. I’d like to think I saw a hint of actual dismay in her eyes, and though it makes me sick to admit it I kind of wanted her to feel that way, to experience her own form of a let-down, to realize for once that this is how most people treat one another.

Needless to say, that was my last attempt at online dating.

☽☾ ☽☾ ☽☾

Isn’t it terrible how easily we let other people control what we do? The comedian actually has this insightful bit where he goes around committing all these petty crimes and then gets away with them in court when he successfully blames his misdeeds on other people. “I’m not responsible,” he tells the judge, “because my Driver’s Ed teacher didn’t properly explain the carpool lane to me.” Or “I saw on the news that up to 11 percent of subway riders don’t pay the fare.” Or “last week a fortune cookie told me I’d receive an unexpected financial windfall.”Each time the judge apologizes to the comedian, sets him free, and directs the bailiff to go hunt down the Driver’s Ed teacher, or the newscaster, or the fortune cookie writer. The routine is absurd, but it’s also kind of poignant, because most of us would actually prefer to let someone else be responsible for our lives rather than have to live them all on our own.

Which is why, when the comedian comes to town one weekend to perform, even though I want nothing to do with him, even though his show is the last place on earth I want to be, I agree to go see him. I spend $250 on a brand new three-piece suit, and I wear it to the comedian’s show.

Because of Josie.

“We really should go,” she said to me when the tickets went on sale. “What if you wore a suit? People would think you’re part of the show. It’s the perfect way for you to get over this silly anxiety of yours. Who knows, it might even help you meet someone.”

In my head, I know it’s a terrible idea. In my head, it’s the equivalent of walking around in a shirt that says:

⇧

Inferior Substitute

(not actually what you were hoping for)

But when Josie insists I give in without much of a fight.

“Please just try it?” she says. “And if it doesn’t help, I’ll never ask again. I promise.”

So we go to see the comedian. The show is at one of those old-time ornate theaters, with cushy pink carpet everywhere and fancy gold-colored molding along the walls. We show up and stand together out in the lobby, waiting for the doors to open, and immediately people start staring. Some point and others whisper. Eventually they start coming up to us. You can actually feel a buzz of excitement spread throughout the lobby, and the buzz is directed toward us. It’s like I’m the opening act or something. Even after people realize I’m not him, they don’t leave us alone. They ask me to tell a joke or take a selfie with them. And it’s not even them I mind so much. It’s the people who hang back, who don’t approach us but still take photos from afar, still talk about me loud enough to hear. Those are the people who make me feel like I’m a sideshow, like I’m grabbing for popularity I haven’t earned. Occasionally, Josie reaches out and squeezes my hand, or whispers in my ear, “You’re doing great,” and it’s the only thing that keeps me from bolting.

After what feels like forever the theater doors open and everyone heads for their seats. Ours are much closer than I would have preferred, 15 rows back on the far left-hand side, and the couple sitting next to us on my left are the last people to torment me before the house lights go down.

“We saw you in the lobby!” the woman squeals.

“Are we going to be part of the show?” her husband asks excitedly, but then the audience begins to clap. The real comedian has arrived, and I finally get some relief.

Fifteen minutes into the show, the comedian is doing this juvenile shtick about how if he were ever in a porno he’d require his own stunt double, when suddenly the guy next to me starts calling out, “But your stunt double’s already in the building!”

No one pays him much attention, but I know what he’s trying to do. “Please,” I say. “Just stop.” But he doesn’t. He keeps calling out until finally the comedian has to acknowledge him.

“Ooh, we’ve got a heckler, ladies and gentlemen,” he calls out from the stage. “What the fuck can I do for you, pal? We’re trying to do a show here.”

“Your stunt double is sitting right here,” the guy next to me says, and I can start to feel this boiling anxiety rise in my chest. “And he’s much funnier than you are.”

“What?” The comedian calls out. “First, fuck you for interrupting. Second, can we get a spotlight over there, find out what this asshole’s talking about?”

A spotlight shifts to our row. The guy to my left is pointing me out, and everyone, the entire theater, is focused directly on me. It feels like the entire world.

“Holy shit,” the comedian calls out when he sees me. “Ladies and gentlemen, my evil twin is in the house tonight. Come on up here, man. Let’s get a good look at you.”

The comedian starts waving me toward the stage. The guy to my left tugs at my sleeve. People begin slow-clapping. And of course Josie starts pushing me toward the aisle. “Go for it. Go!” she calls out into my ear. There’s nothing I can do. I rise and start walking toward the aisle. The anxiety in my chest is practically bursting through my ribs. People are clapping, and there’s this rush of energy to the point where I feel almost numb.

Adrenaline drives me up the stairs onto the stage, and all of a sudden I’m overwhelmed with a feeling of heat, radiating from the lights above and from the gaze of hundreds of eyes in front of me. The comedian greets me, wraps his arm around my shoulder and directs me toward his microphone.

“Welcome to the stage, pal,” he says. “You know, I’ve dealt with a few stalkers in my time, but this—growing out the hair and the beard, putting on weight—might be a new low. My compliments to your plastic surgeon.”

He reaches into the inside of my jacket and grabs hold of the label. “This psycho even got my jacket size correct!” he shouts out.

Everyone is laughing, and I can feel the laughter crushing down upon me. A small part of my brain is going, Say something! Say something! But every other fiber in my body is just flat-lining, like, —–.

“I have to admit, you’re a handsome gentleman,” the comedian says to more laughter. “But you are dumb as a post.”

Laughter, and —–

“I guess we know which conjoined twin got the brains after the operation.”

Still laughter, still —–

“Seriously man, have you been fooling around with my wife? Maybe this is why she says I’m so boring in bed.”

—–

“Nothing? OK. That’s enough,” he says, and gently pushes me back toward the audience. “We’ve had our fun. Now get this asshole who isn’t me off the stage.”

I stumble my way off, back down into the darkness of the audience. I quickly make my way back to my row, where the guy sitting next to me greets my return with two thumbs up. “Nice work, buddy,” he says. I slump into my seat, still hot, still breathing heavily, and instinctively reach for Josie’s hand. She grabs it and leans in. She is laughing.

“You did so great,” she says. “I’m proud of you. I mean, how funny was that!”

She lets go of my hand and returns her attention to the comedian. He has already moved on, returned to his material. Mercifully, the audience has forgotten me.

☽☾ ☽☾ ☽☾

People say communication is a cornerstone of a healthy relationship. You need to be able to communicate in order for a relationship to last. People also say things like, if you’re nervous lead with a joke, or laughter is the best medicine. Which kind of implies that humor is a valid approach for this whole communication thing. Well, my friend Josie is the funniest person I know, and yet sometimes I think we struggle to communicate properly. Here’s a perfect example: after the comedian’s show—the one where I let myself get pressured onto the stage then panicked and froze up and was publicly humiliated and almost pissed my new suit—my energy is absolutely drained. The last thing I want to do is be around other people. But when Josie suggests we go out for drinks, I just nod and follow along. We go to this real grimy kind of place, this total dive bar, and I’m still dressed in my three-piece suit, feeling all itchy and constricted and discouraged. And she’s smiling and grooving to the music and talking to people, having a great time.

After a few drinks I say to her, “I’m thinking about shaving my beard.”

She laughs, of course, because she thinks everything I say is a joke. “No way, man!” she says. “Don’t do that. It’ll ruin your whole look! If this is your not-so-subtle review of the show, don’t worry about it. Everybody was laughing with you. It’s not a big deal.”

“Well, I’m definitely getting a haircut,” I say. “It’s time I started looking more professional.”

She laughs again and starts tussling my hair. “Never!” she says. “I won’t allow it!”

“Will you marry me, then?” I say.

She cocks her head a little and purses her lips into one of those scolding kinds of looks. “Come on,” she says, “you can stop trying to be funny. You already had your chance up on stage. It’s too late now.”

“I didn’t ask for any of this,” I say. “I didn’t ask to look like this, or for this guy to just show up and make me change who I am.”

She laughs nervously and shrugs, hoping the conversation will end there. But I’ve already begun to point out the obvious. There’s no going back now.

“Marry me,” I say. “Marry me, or I never want to see you again.”

She stares back at me. “You’re not actually serious, are you?”

“Can’t I be serious for once?” I say. “If this wasn’t a bar full of people, if I wasn’t wearing this ridiculous suit, if we weren’t joking around and I actually got down on one knee and proposed, what would you say?”

Communication, right? Finally telling someone exactly how you feel? No more wading through bullshit? Communication is all it takes, apparently, because after I deliver that rousing speech she pulls me in close and whispers “yes” into my ear, then gently nudges me down onto one knee. People around us start to realize what’s going on; they all stop their conversations and someone starts clapping and pretty soon the entire bar is clapping for us.

Now that’s pretty cool. That’s a big-time moment, right there. I mean, it would’ve been a big-time moment if that’s what had happened.

But of course that’s not what happened. What happened is, she actually does pull me close to whisper in my ear, only she has a look in her eyes of just pure pity and sorrow—like how veterinary techs at the pound must look every time they have to put down a dog—she gives me that look, and she can’t really whisper because the music is so loud, so she’s practically shouting and says, “I’m so sorry. I’m—I don’t know how else to say this. I just don’t—no,” she says, and shakes her head. “I know that’s not what you want to hear, but—I’m sorry.”

And I’m standing there thinking to myself, that was very well communicated on your part. Thank you.

She pecks me on the cheek, which for me felt pretty much like how I’d imagine the dog feels when the veterinary tech is putting it down, and tells me she’d better go, but she’ll see me soon. And then takes off. A total sweetheart to the end.

As for me, of course I should go home, but instead I stay out at the bar drinking and drinking like a maniac, and I’m sitting there with my head buried in my phone and at some point, this girl is standing next to me, trying to flag down the bartender to order a drink. She turns and says to me, “Long night at the office, huh?”

I’m pretty drunk at this point, probably mumbling incoherently, but what I’m actually thinking to myself is, which joke is this? Which of the comedian’s bits are we doing? What’s his next line, what am I supposed to say here?

“I meant your suit,” she says, pointing at me. “You’re wearing a suit in a bar at 12:30 in the morning. The natural assumption is: you must have come straight from the office.”

“Oh,” I say. “Sorry, I thought you might have recognized me from someplace.”

She shakes her head. “I don’t think so, no.” There’s one of those awkward pauses, then, where neither of us have any clue what to say to the other. She keeps looking for the bartender to show up and save her from the silence, but I’m sitting there thinking, this silence is golden. I could probably sit here and live with this silence for the rest of my life. But it’s too much for her, apparently, because finally she breaks down and asks, “So what kind of work do you do, then, if you didn’t come from an office?”

“Well,” I say to her with a sigh. “I’m a comedian.”

She doesn’t say anything, just stands there unsure of how to respond, so finally I ask her: “Do you want to hear a joke?”